Symbolism, Imagery, Allegory

(Click the symbolism infographic to download.)

Much of the novel's beautiful imagery is rooted in Cather's physical descriptions of the Nebraskan landscape. Let's take a look at one of Jim's early reactions to the American West:

There seemed to be nothing to see; no fences, no creeks or trees, no hills or fields. If there was a road, I could not make it out in the faint starlight. There was nothing but land: not a country at all, but the material out of which countries are made. No, there was nothing but land--slightly undulating, I knew, because often our wheels ground against the brake as we went down into a hollow and lurched up again on the other side. I had the feeling that the world was left behind, that we had got over the edge of it, and were outside man's jurisdiction. I had never before looked up at the sky when there was not a familiar mountain ridge against it. But this was the complete dome of heaven, all there was of it. I did not believe that my dead father and mother were watching me from up there; they would still be looking for me at the sheep-fold down by the creek, or along the white road that led to the mountain pastures. I had left even their spirits behind me. The wagon jolted on, carrying me I knew not whither. I don't think I was homesick. If we never arrived anywhere, it did not matter. Between that earth and that sky I felt erased, blotted out. I did not say my prayers that night: here, I felt, what would be would be. (1.1.10)

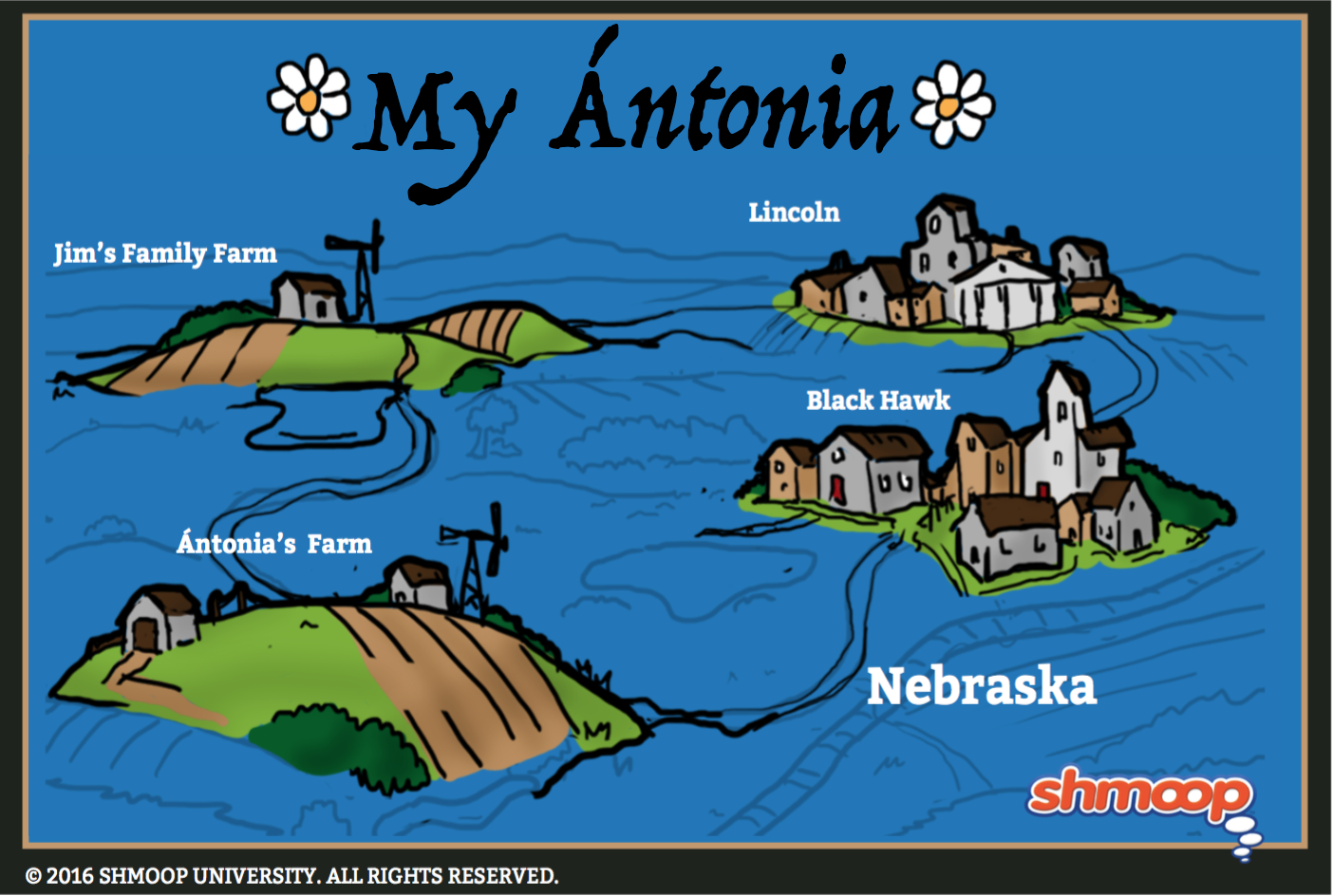

(Click the map infographic to download.)

(Click the map infographic to download.)

This new environment marks the beginning of an adventure for Jim in more ways than one. His parents have just died and so he is an orphan – he's embarking on adulthood alone. The country, too, is in a sort of pre-adolescent stage – at least out in Nebraska. The land is still being populated by all sorts of new-comers (think immigrants like the Shimerdas), and it is "not country, but the materials out of which countries are made." In a way, this is a symbol for Jim's own status as he prepares to grow into a man. The vastness of adulthood stretches before him, not unlike the vast Nebraskan prairie land.

As the novel continues, the landscape and the natural elements play an enormous role in determining the actions and moods of the characters. Mr. Shimerda, for example, commits suicide after a particularly difficult winter. Later in the novel, Ántonia finds it odd that the man who jumped into the threshing machine chose to kill himself when the weather was so nice. Part of the reason for this connection is that the novel is set in a time and place where the weather places practical limitations on the characters. As a result, the characters are simply more in tune with the weather and the natural elements in general:

The pale, cold light of the winter sunset did not beautify--it was like the light of truth itself. When the smoky clouds hung low in the west and the red sun went down behind them, leaving a pink flush on the snowy roofs and the blue drifts, then the wind sprang up afresh, with a kind of bitter song, as if it said: `This is reality, whether you like it or not. All those frivolities of summer, the light and shadow, the living mask of green that trembled over everything, they were lies, and this is what was underneath. This is the truth.` It was as if we were being punished for loving the loveliness of summer. (2.6.2)

Jim's thoughts on this particular shifting of the season embody these connections between man and the natural world portrayed in this novel.